The rise of mass and universal forms of higher education has led to the growing debate, research and theorisation of student engagement. Students are now expected to adhere to institutionalised and behavioural-based definitions of engagement, yet limited research exists that explores students’ perceptions and definitions of engagement. This article represents a first step in defining student engagement from the perspective of the student. Notions and definitions of engagement were gathered through focus groups with students on the BA (Hons) Fashion Public Relations and Communication course at London College of Fashion. The students’ definitions of engagement were then used to design teaching sessions to improve learner engagement based on the students’ own parameters. The results relating to each teaching method aligned with the students’ pre-test definitions of engagement and highlight the array and complexity of discipline specific factors that influence student engagement in art, design and communication based courses.

student engagement, pedagogies of engagement, media and communications, rhetoric, experiential learning, problem-based learning

Those working in the enhancement of learning and teaching have long understood the importance of students’ engagement with their learning, but it is only recently that awareness has increased, affecting public discourse around educational quality. Now a pervasive buzzword, a debate continues over the definition and ‘object’ or focus of student engagement (Ashwin and McVitty, 2015). Defined by Krause and Coates (2008) as the contribution that students make towards their learning, as with their time, commitment and resources, engagement is linked to retention and attainment in higher education (Kahu, 2013).

The term is currently used to refer to student engagement in learning activities, in the development of curriculum and in quality assurance and institutional governance (Ashwin and McVitty, 2015; Macfarlane, 2015). Kahu (2013) found that there exists four distinct approaches to understanding engagement: the behavioural perspective, which is centered in effective pedagogy; the psychological perspective, which defines engagement as an internal individual process; the sociocultural perspective, which argues that student retention increases when there is ‘academic and social integration’ (Gibbs, 2014); and the holistic perspective, which tries to unite the previous three approaches.

The most widely accepted definition of engagement is the behavioural perspective, which highlights student behaviour and teaching practice (Kahu, 2013). The focus in higher education is now on challenging students to invest time and ‘intellectual energy’ in their course (Buckley, 2014). Engaging students in learning is now widely discussed as principally the responsibility of the teacher, who moves from imparting knowledge to designing and facilitating learning experiences (Smith et al., 2005).

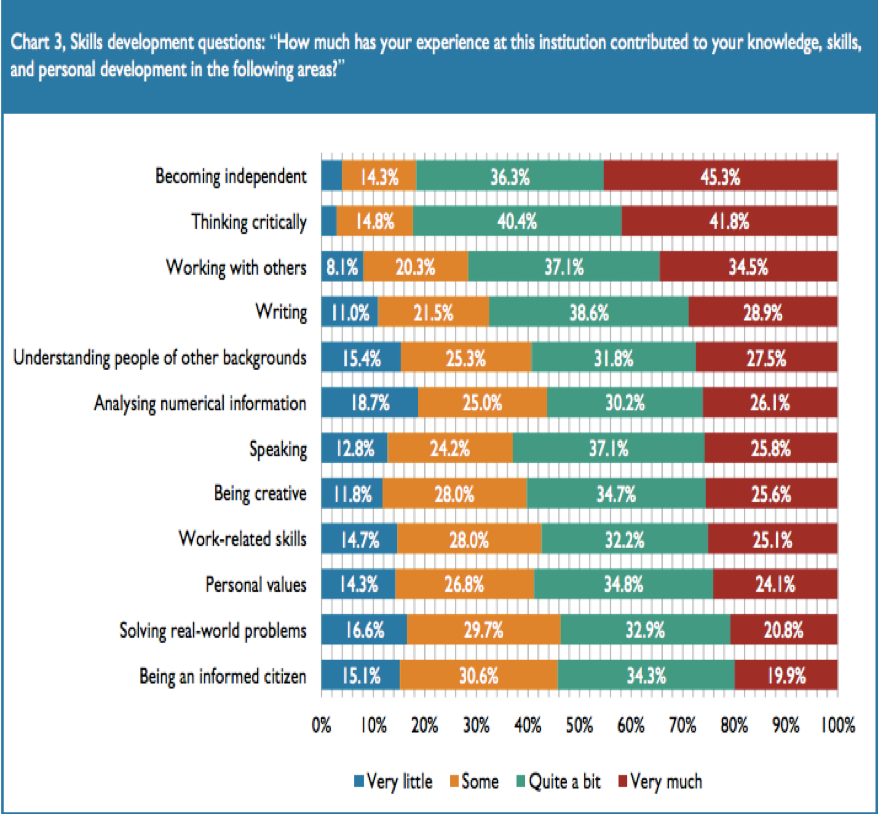

Governments are increasingly interested in measuring student outcomes (Kahu, 2013). This is reflected in the proposed inclusion of items on engagement in the UK’s National Student Survey as well as in the second pilot of the UK Engagement Survey in 2014 (Buckley, 2014). The key variables that make up student engagement have been captured in the second pilot of the 2014 UK Engagement Survey, which found that the areas least developed through educational experiences are ‘being an informed citizen’ and ‘solving real-world problems’ (Buckley, 2014).

Figure 1: Buckley (2014) UK Engagement Survey 2014: The Second Pilot Year.

The use of surveys as a measurement tool is a key limitation of the behavioural perspective, particularly when measuring teaching and learning across different disciplines (Kahu, 2013).

Macfarlane (2015) argues that the push in increasing student engagement has led to ‘performative pressures’ on students who have entered a voluntary phase of education. Students are now expected to adhere to institutionalized and behavioural-based definitions of engagement (Kahu, 2013; Macfarlane, 2015). This includes demonstrating more visibly that they are learning through participation in class, sharing their ideas in public discussions and being prepared to take part in community-based projects that demonstrate shared normative values (Macfarlane, 2015). The rise of student performativity is also explained by the greater emphasis on practitioner-based and professional skills due to the expansion of vocationally oriented subjects within the university curriculum. Macfarlane (2015) claims that this has infringed on the rights of students to shape their own individual learning experience, to be vocal or quiet in sessions and develop their own ideas and values. ‘What it means to be a student, not just the product of their intellectual endeavours undertaken in private, is now observed and evaluated’ (Macfarlane, 2015, p.339).

Limited in-depth research exists into exploring students’ perceptions and definitions of learner engagement, beyond the questionnaire approach (Kahu, 2013). Current research does not cover the array of factors that influence student engagement, and there is a lack of in-depth studies that look at specific student populations and university subjects (Kahu, 2013). This study explores how ‘communication’ students on the BA (Hons.) Fashion Public Relations and Communication course (London College of Fashion) perceive learner engagement and how engagement can be improved based on these parameters. In the first section of this article, students’ perceptions and definitions of engagement were gathered through the use of focus groups. The second section then considers the students’ definitions of engagement, as well as pedagogy of engagement theories, which were used to design teaching sessions that promote active learner involvement.

The approach used in conducting this investigation involved action research. This allowed for the systematic inquiry of engagement from the perspective of the students (Kreuger, 1988). Data collection included a focus group with eight, year 1, female students on the BA (Hons) Fashion Public Relations and Communication course (LCF): five international students and three home/EU students. The focus group relied on volunteers who were willing to express opinions, perspectives and attitudes about their experiences (Cohen, 2000).

The use of a focus group format provided greater flexibility than the survey method as it allowed for the clarification of questions and follow-up queries to dissect vague or unexpected responses (University of Sheffield, 2015; Krueger, 1988). This method also allowed for the exploration of diverse perspectives and issues in a short period of time and was effective when identifying agreement across the groups and for eliciting suggestions for improvement (Cohen, 2000; Kreuger, 1988).

The focus group questions were designed to collate the students’ definitions of engagement, asking what makes learning easier for them; what makes it impossible; what switches them on and off; and how they know when they are engaged. Students were asked to sign a consent form confirming voluntary participation, outlining that the use of this information was confidential and for the purposes of research only. An ethical review form was completed based on the University of the Arts’ research guidelines.

Limitations of this focus group method included relying on student volunteers. This may have introduced bias, as other students who have become disengaged with their learning experience may be less likely to volunteer (Cohen et al., 2000). Some of the students who participated also focused on negative experiences, using this group as an opportunity to discuss their grievances (University of Sheffield, 2015).

Results were analysed using descriptive statements, which summarised the students’ comments and provided illustrative quotes utilising the raw data (Kreuger, 1988). Definitions of engagement centred on understanding a concept well enough to explain it to someone rather than trying to memorise it. Several students expressed that they felt engaged in a teaching session on current and relatable brand examples, when given the opportunity to apply taught theory to a real brand issue. Students placed a high value on building competencies that prepare them for industry and wanted to learn through problem-based learning, which replicated the experience of being a practitioner. They mentioned that they wanted work that challenged them and encouraged them to think for themselves. They felt their in-session engagement increased when the task was creative in nature and had a tangible outcome and provided the example of completing brand mood boards or creating look books. Two students in the group also highlighted their shyness, and expressed that engagement for them meant observing and listening rather than actively interacting and speaking in a session. This illustrates the problematic nature of labeling non-oral participation, such as eye contact, note taking and active listening, as ‘passive’ or negative forms of learning (Macfarlane, 2015; Nonnecke and Preece, 2000).

The students also yearned for more challenging questions, further time for discussion and questions, and more meaningful learning opportunities. This was underpinned by a need for greater social interaction within the cohort, further involvement in college/university activities and initiatives, interaction with students on other courses, and more time spent at university.

Student contribution in course design provides students with an element of control and greater investment and empowerment in the learning process (Chang et al., 1998). This second section undertakes a review of media and communications pedagogy and pedagogies of engagement. It considers two methods of pedagogies of engagement, which have been chosen as a result of the student responses and act as a review of the literature used to analyse them. These methods were used to reflexively design the teaching sessions.

Communication scholars have traditionally focused on the idea of communication as merely a conduit for a message, and this thinking underpins much pedagogic practice in the discipline (Motion and Burgess, 2014). Communications pedagogy is often focused on the ‘transmission’ of knowledge and theory, however, communications at the strategic level involve problem solving, which requires critical reflection, interrogation and thought (McKie and Munshi, 2009).

In fashion communication pedagogy, students must be encouraged to look at communication as culture: part of a system of cultural practices that create, maintain and change society (Fernback, 2015). It is important to look at how communication both challenges and creates social tensions such as sexism or ageism. Students should question the storytellers (brands) and reflect on the meanings of messages (Fernback, 2015). Media and communication educators must also challenge the perception that ‘the media’ is the primary source for disseminating messages, while encouraging reflection and stimulating critique (Motion and Burgess, 2014). As Stokes and Waymer have observed, being ‘technically proficient without being able to make informed contributions to debates about contemporary society leaves student training incomplete’ (2011, p.442). Students need to know how their discipline shapes, and is affected by, culture and citizenship (Motion and Burgess, 2014).

The term ‘pedagogies of engagement’ was introduced in Russ Edgerton’s 2001 publication, Education White Paper (Smith et al., 2005). This theory is based on the belief that teaching in university is not about covering the material for the students; it is instead concerned with ‘uncovering the material with the students’ (Smith et al., 2005).

Educators, researchers and policy makers have advocated methods of ‘student centred learning’ and active student participation, such as problem-based learning as an essential aspect of engagement and deep learning (Macfarlane, 2015; Shreeve et al., 2010). The student-centered approach has performative expectations based on the social constructionist philosophy (Macfarlane, 2015). This is based on the belief that students should be seen ‘publicly’ to be learning and constructing a personal understanding instead of acquiring knowledge as a ‘private’ activity (Macfarlane, 2015; Holmes, 2004, p.627).

Problem-based learning has been widely discussed as a method of engagement in pedagogical practice. Problem-based learning (PBL) is learning that results from the process of working towards understanding or resolution of a problem (Smith et al., 2005). In problem-based learning, teachers are facilitators or guides, learning is student-centered and self-directed and occurs in small groups (Barrows, 1996).

Shreeve, Sims and Trowler discuss problem-based learning in the context of learning in art and design as ‘Preparing for Practice’. Their view is that students learn through replicating the experience of being a practitioner (Shreeve et al., 2010). The tutor’s role therefore is not to produce students who can recite a fixed canon of knowledge, but to develop students who understand where they and their work fits and belongs within a discipline (Shreeve et al., 2010). In their 2014 article on transformative learning approaches, Motion and Burgess found that an introductory course in ‘media and communication’, which focused on teaching abstract concepts of social-theory, was not initially perceived to be meaningful. It was only when students were able to apply these concepts to a real client project that meaningful learning took place.

Case studies are a form of PBL that are proven to be effective methods of engagement in teaching today's ‘millennial’ generation, allowing for greater engagement with unit learning outcomes and retention of material (Baturay and Bay, 2010). Completing case studies in groups also allows students to engage in cooperative interaction. This encourages them to teach course material to one another and to dig below superficial levels of understanding of this material being ‘taught’ (Meyers and Jones, 1993).

Pedagogies of engagement also promote ‘experiential learning’; learning encouraged through experience (Benecke and Bezuidenhout, 2011). Experiential learning activities can include practical experiences and classroom‐based, hands‐on tasks such as simulated, on‐campus and community involvement projects (Benecke and Bezuidenhout, 2011). Kolb (1984) found that learning requires the resolution of conflicts between dialectically opposed modes of adaptation to the world and that conflict, differences, and disagreement are what drive the learning process. Kolb also proposes a ‘constructivist’ theory of learning whereby social knowledge is created and re-created in the personal knowledge of the learner. This theory is in contrast to the ‘transmission’ model often used in much communications based pedagogy, which outlines pre‐existing fixed ideas are transmitted to the learner.

Two teaching sessions were then designed using theories of pedagogies of engagement as well as the responses from the student focus groups:

Session 1: Problem-Based Learning, through the use of a case study

Session 2: Experiential Learning, using rhetorical instruction as a means of teaching PR students to be thoughtful, ethical, and reflective practitioners.

Problem-based learning was utilised in the first session through use of a case study. This method allowed the students to apply the taught theoretical concept — a PR and communication audit — and develop recommendations and communication-based solutions to a real brand issue. The problem faced by the brand was the organising focus and stimulus for learning (Barrows, 1996).

The students were first led through a theoretical discussion in a lecture on completing a PR/communication audit using five key steps. The students were divided into groups of four, and provided with a case study on UK designer brand Meadham Kirchoff.

Each group was provided with iPads to undertake online research on the brand in order to complete the audit. The students dissected the ways in which this brand communicates, using the five steps of auditing covered in the theoretical discussion. A team leader then briefed the rest of the group on their findings. In the session, learning occurred in the student groups.

The case study brought up complex issues currently impacting the industry: ‘We are entering a no-man’s land of drone-like fashion and conveyor belt creativity. We need to be careful that we don’t eradicate the very reason that makes us do what we do.’ (Lau, 2014). A lively discussion emerged about the strengths and weaknesses of Meadham Kirchoff’s communication strategy; the machine that has become the industry; and what the brand is not capitalising on (the strength of brand fans, as well as the importance of direct-to-consumer communication strategies). Group facilitation stimulated further questions, perspectives and ways to look at the case study.

Student reflection was sought through questions immediately following the teaching sessions, based on the concept of the minute paper, a formative assessment strategy whereby students are asked to take one minute (or more) to answer two questions (Stead, 2005). The goal is for the instructor to get a feel for whether students had captured the most important points. Nineteen of the Year 1 students recounted their experiences during the session through two reflection-based questions. The students’ definitions of engagement centred on their ability to explain something to someone else, the application of this learning to real life and coming up with solutions to real brand problems.

The first question was designed to measure the students’ ability to explain a concept to someone else: a method that is widely discussed as a key form of engagement in learning (Smith et al., 2005). Students were given five minutes to write their response to the following questions.

The complex issues in the case study (asking if designers can continue to keep up with the never-ending cycle of fashion) allowed students to think about their role as practitioners who will shape the future of the industry, adding another layer of analysis and reflection. There was energy in the room based on the varying beliefs and values that came into play.

This exercise allowed students to conduct a communication audit on a ‘real world’ example, enacting what it means to be a practitioner, which was also an important factor of their engagement, as indicated by the discussions of the focus groups, ‘The case study effectively exemplified how to do an audit in real life.’ Students also outlined that ‘case studies are quite useful since it helps with having a better understanding of concepts, theories and subjects being studied.’

Student reflection on the session also unveiled improvements that could be made. The student feedback mentioned that they wanted greater time to complete their own research on the brand used in the case study (indicating that they should be given less information on the brand’s background initially). The students also mentioned that they wanted the chance to explore the case study first and then audit the brand without being provided with the steps in conducting the audit.

‘The case study was helpful for application, but I would have preferred to of done it before the slides as they were laid out on the sheet [case study].’

‘Allowing more time to walk through the case study as a group would have been more effective in exploring the concept of auditing rather than teaching it first.’

‘I liked the case study in teaching industry skills, but it would have been better if we did it at the beginning of the session.’

The second teaching session utilised methods of experiential learning through rhetorical instruction – an effective approach to teaching communications students the critical thinking skills needed to be thoughtful, ethical, and reflective practitioners (Stokes and Waymer, 2011). Exposing students to rhetorical discussion can help to ‘prepare students for practice and prepare students to both understand and interrogate public discourse’ (Stokes and Waymer, 2011, p.441).

The students were led through a discussion on rhetoric, which included terministic screens using theory from Heath, Burke and Aristotle. They were then assigned reading on these concepts with theory from Heath (1997) and a case study on Chanel’s use of a feminist protest for their Spring/Summer 2015 runway presentation, which questioned the brand’s message in relation to feminism and possible appropriation.

The Chanel case study was utlised in order to encourage the students to think about how brands shape and respond to cultural trends and public discourse and develop their understanding of how this discipline is engaged in a rhetorical process that builds society.

The students were asked to read the case study and answer three questions during their self-directed study time. This allowed for the work and analysis to be done outside of the classroom, so that the session could be used to analyse and deconstruct their findings. This approach provided the students with autonomy in shaping their own learning experience. In the follow-up session, the students discussed these three questions in pairs. A group discussion was facilitated and observed.

Session 2 was measured through observation of the 31 students, whilst they engaged in a facilitated discussion. In this exercise, students were able to apply rhetoric to a real world example of a brand’s communication strategy. Instead of learning the strategies and tactics used in communication from a surface level, this exercise allowed the students to dig below superficial levels of understanding, often created by the material being taught to them in a traditional sense (Meyers and Jones, 1993).

The session catalysed an active debate about how brands appropriate culture and subculture. Students highlighted examples such as Alexander McQueen’s political narrative in his Highland Rape collection and unpacked the multiple meanings of brand campaigns. Rather than transmitting pre-existing, fixed ideas to the students through a lecture format, material was uncovered with the students. Social knowledge was created and recreated in the personal knowledge of the learner (Kolb, 1984) allowing them to resolve conflicts based on their own view of the world.

Several students identified the use of rhetoric (terministic screens) by Chanel using the historic, feminist ideals of Coco Chanel, and labeled the campaign as the appropriation of feminism. The students discussed the importance of authenticity and sincerity when a brand or designer references cultural and political movements, using the example of designer Hussein Chalayan, who referenced displacement in his runway show (Chalayan is a Cypriot who has been displaced himself).

During the course of the discussion, several students said that they struggled with self-directed reading and in understanding the terministic screens, and had to spend extra time working through these concepts. This difficulty and confusion enriched the session, encouraging them to work outside of their comfort zones and allowing them to think about their discipline more deeply. Students began to explore how communication simultaneously challenges and creates social tensions; unveiling how Chanel attempted to reframe the function and process of purchasing product from a frivolous and soulless experience to one that was focused upon expressing values and connecting with others (Katz, 1960; Smith et al., 1956).

The focus groups and sessions described in this article represent a first step towards defining student engagement from the perspective of the student: asking students to explicitly engage with engagement. Notions and definitions of engagement were gathered through focus groups with students on the BA (Hons) Fashion Public Relations and Communication course at LCF. These focus groups facilitated a candid and personal discussion with the students, ascertaining when they feel engaged and what makes learning best for them. Common answers included ‘when you can explain something to someone else’, ‘case studies and coming up with solutions to real brand problems’ and ‘putting a recent campaign up, and then analysing the campaign’. Students placed a high value on building competencies that prepare them for industry. Students also mentioned that when they are engaged they are quiet and reflective, which illustrates the problematic nature of labeling non-oral participation, such as eye contact, note taking and active listening, as ‘passive’ or negative forms of learning (Macfarlane, 2015).

The students’ definitions of engagement, supported by theory on pedagogies of engagement, were then used to design two teaching sessions: problem-based learning through the case study method and experiential learning using rhetorical instruction. Feedback from these sessions implies that the students were able to explain what they had learned in the session. Both methods included case studies, which allowed the students to solve real brand issues through the application of a theoretical concept. The case study method improved students’ retention of the material and, because it was assigned as a self-directed study activity, it meant that students were learning outside of the classroom and bringing their thoughts to the session, ready for discussion and debate. Completing case studies in groups within the sessions also allowed students to engage in cooperative interaction, teaching course material to one another and digging below superficial levels of understanding of the material being taught. The group was empowered, auditing the brand and enacting what it means to become a practitioner, while having the confidence to come up with a suggested strategy.

Complex theory on rhetoric and the appropriation of culture by fashion brands, encouraged students to engage in a wider discourse and develop discipline specific and conceptual thinking skills. The students were able to question the storytellers (brands), reflect on the ‘meanings of messages’ and consider communication as culture (as part of a system of cultural practices that create, maintain and change society). Feedback from the session ascertained that students wanted the chance to explore the case study prior to being taught the theory.

The limitations presented by this research method occur from its reliance on student volunteers to form the focus groups, which may have introduced bias. Those who have become disengaged with their learning experience may be unlikely to volunteer (Cohen et al., 2000). Students also utilised the focus group as an opportunity to discuss their grievances and often reflected on negative experiences. Balancing this group data with insights gained through individual feedback may, upon reflection, have mitigated the risk of some participants saying what they though others in the group wanted to hear (University of Sheffield, 2015; Cohen et al., 2000). Moving forward, additional studies using larger and more diverse student focus groups are a necessary means to reinforce and develop the initial findings of these sessions.

This research did not measure an increase in engagement, but was a form of reflexive teaching using the students’ own definitions in order to design teaching sessions. In this study, engagement and academic integration have been explored from a pedagogical perspective rather than from a sociological perspective. It has not explored or tested the impact of social integration, for instance the close relationships between peers, involvement with college/university-based activities, events or initiatives outside the classroom. Further studies could allow students to outline and rank factors that increase their engagement. Furthermore, students could be provided the chance to design their own sessions based on these factors and write their own case studies. Uncovering the causes of (or processes involved) in engagement is challenging. Engagement involves implicit knowledge and opinions, which take shape during during an extended period of time and involve less straightforward research methods.

Anyangwe, E. (2011) ‘Putting student engagement at the heart of HE – live change best bits’, The Guardian, 26 October. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2011/oct/26/student-engagement-tips (Accessed: 10 February 2015).

Ashwin, P. and McVitty, D. (2015) ‘The meanings of student engagement: implications for policies and practices’, in Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopie, R., Salmi, J. and Scott, P. (eds.)The European higher education area: between critical reflections and future policies. Cham: Springer, pp. 343–359.

Barrows, H.S. (1996) ‘Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview’, in Wilkerson, L. and Gijelaers, W.H. (eds.) New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 68. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, pp. 3–11.

Baturay, M.H. and Bay, O.F. (2010) ‘The effects of problem-based learning on the classroom community perceptions and achievement of web-based education students’, Computers and Education, 55(1), pp. 43–52.

Benecke, R.D. and Bezuidenhout, R.M. (2011) ‘Experiential learning in public relations education in South Africa’, Journal of Communication Management, 15(1), pp. 55–69.

Buckley, A. (2014) UK Engagement Survey 2014. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resource/uk-engagement-survey-2014 (Accessed: 9 December 2015).

Burke, K. (1966) Language as symbolic action: essays on life, literature, and method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chang, J.L., Piket-May, M.J. and Avery, J.P. (1998) ‘Using active student feedback in the learning environment’, in 28th annual Frontiers in Education conference, Vol. 2. Illinois: IEEE/Stipes Publishing, pp. 643–646.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. (2000) Research methods in education. 5th edn. London: Routledge Falmer.

DiStaso, M. W., Stacks, D.W. and Botan, C. H. (2009) ‘State of public relations education in the United States: 2006 report on a national survey of executives and academics’, Public Relations Review, 35(3), pp. 254–269.

Fernback, J. (2015) Teaching communication and media studies: pedagogy and practice. New York: Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (2014) ‘Student engagement, the latest buzzword’, Times Higher Education, 1 May. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/news/student-engagement-the-latest-buzzword/2012947.article (Accessed: 2 April 2015)

Heath, R. L. (2001) ‘A rhetorical enactment rationale for public relations: the good organization communicating well’, in Heath, R. L. (ed.) Handbook of Public Relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 31–50.

Khan, S. (2012) Why long lectures are ineffective. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2012/10/02/why-lectures-are-ineffective (Accessed: 3 March 2015).

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kahn (2014) ‘Theorising student engagement in higher education’, British Educational Research Journal, 20(6), pp. 1005–1018.

Kahu, E.R. (2013) ‘Framing student engagement in higher education’, Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), pp. 758-773.

Krause, K. L. and Coates, H. (2008) ‘Students’ engagement in first-year university’, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33 (5), pp. 493–505.

Krueger, R. A. (1988) Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Lau, S. (2014) ‘What does Meadham Kirchoff’s struggle say about the fashion industry?’, i-D, 22 December. Available at: https://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/article/what-does-meadham-kirchhoffs-struggle-say-about-the-fashion-industry (Accessed: December 2015).

Macfarlane, B. (2015) Student performativity in higher education: converting learning as a private space into a public performance, Higher Education Research & Development, 32 (2), pp. 338–350.

McKie, D. and Munshi, D. (2009) ‘Theoretical black holes: a partial A to Z of missing critical thought in public relations’, in Heath, R. L., Toth, E. L. and Waymer D. (eds.), Rhetorical and critical approaches to public relations II. New York: Routledge, pp. 61–75.

Meyers, C. and Jones, T.B. (1993) Promoting active learning: strategies for the college classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Motion, J. and Burgess, L. (2014) ‘Transformative learning approaches for public relations pedagogy’, Higher Education Research and Development, 33(3), pp. 523–533.

Pascarella, E. T., Seifert, T. A. and Blaich, C. (2010) ‘How effective are the NSSE benchmarks in predicting important educational outcomes?’, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 42(1), pp. 6–22.

Poole, S. (2010) ‘The Shallows: how the internet is changing the way we think, read and remember by Nicholas Carr’, The Guardian, 11 September. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/ (Accessed: 4 March 2015).

Shreeve, A., Sims, E. and Trowler, P. (2010) ‘A kind of exchange: learning from art and design teaching', Higher Education Research and Development, 29(2), pp. 125–138.

Smith, K.A., Sheppard, S.D., Johnson, D.W. and Johnson, R.T. (2005) ‘Pedagogies of engagement: classroom-based practices’, Journal of Engineering Education, 94(1), pp. 87–101.

Stead, D.R. (2005) ‘A review of the one-minute paper’, Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(2), pp. 118–131.

Stokes, A.Q. and Waymer, D. (2011) ‘The good organization communicating well: teaching rhetoric in the public relations classroom’, Public Relations Review, 37(5), pp. 441–449.

Todd, V. and Hudson, J. C. (2009) ‘A content analysis of public relations pedagogical research articles from 1998 to 2008: has research regarding pedagogy become less sparse?’, Southwestern Mass Communication Journal, Vol. 25, pp. 43–51.

University of Sheffield (2015) Learning and Teaching Services: Student Focus Groups. Available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/lets/strategy/resources/evaluate/general/methods-collection/focus-groups (Accessed: 9 December 2015).

Weimer, M. (Ed) (2009) Building student engagement: 15 strategies for the college classroom. Available at: http://www.facultyfocus.com/free-reports/building-student-engagement-15-strategies-for-the-college-classroom/ (Accessed: 24 March 2015).

Willisa, P. and McKie, D. (2011) ‘Outsourcing public relations pedagogy: lessons from innovation, management futures, and stakeholder participation’, Public Relations Review, 37(5), pp. 466–469.

Wilson, K. and Korn, J. H. (2007) ‘Attention during lectures: beyond ten minutes’, Teaching of Psychology, 34(2), pp. 85–89.

Emily Huggard is a Lecturer on the BA (Hons.) Fashion Public Relations and Communication course at London College of Fashion. She has worked on strategic fashion communication, marketing and brand strategies across the luxury, menswear and eyewear sectors (both in-house and as a consultant) and on consumer campaigns at Unilever. Her research area explores the impact of artistic collaboration on the brand image of luxury fashion brands.